The Role of the Arms-Bearing Women in Japanese History

Jikishin Kage Ryu Naginata-do and the Development of Meiji Budo

At roughly the same time that Mitamura Kengyo and other teachers were initiating a renaissance in Tendo-ryu, another remarkable school of naginata, the Jikishin Kage-ryu Naginata-do was born. This school claims its roots in Jikishin Kage-ryu sword technique, developed by the famous monk Ippusai out of older Shinkage-ryu sword schools. Ippusai’s ryu, one of the most significant of the Edo and Meiji periods, has deep connections with esoteric and mystical teachings and was one of the first schools to engage in competitive practice with split bamboo swords.

In the 1860s, Satake Yoshinori, a student of the Jikishin and Yanagi Kage-ryu, developed a new naginata school with his wife, Satake Shigeo. She had studied martial arts since she was six years old and was famous for her strength with the naginata. Together they developed the forms of present day Jikishin Kage-ryu naginata-do. An innovative work, it bears no discernible relation to Ippusai’s Jikishin Kage-ryu ken-jutsu. The addition of the suffix “do,” (way) indicates that the founders saw their school as a budo, a means of martial practice for the purpose of self-perfection rather than self-preservation.

The succeeding head teacher, Sonobe Hideo, took Jikishin Kage-ryu into girls’ schools. She taught at major schools in the Kyoto area and was one of the first teachers to popularize mass training. The system has continued to grow and has the most students of any of the traditional schools of naginata. The present head teacher is Toya Akiko.

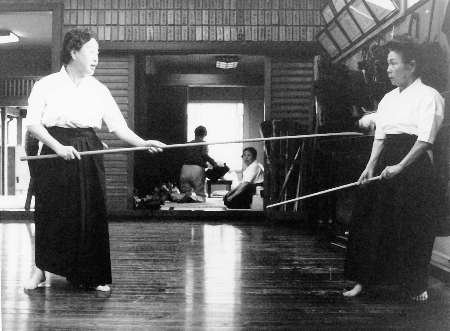

The forms of Jikishin Kage-ryu are done in straight lines in a highly defined rhythm. The kiai is traded back and forth, in almost a call-and-response, adding to a sense of dance-like structure. The forms project a aura of crisp elegance.

The emphasis appears to be on correct performance rather than development of martial skills. When a mistake was made in the practices that I observed, the kata was discontinued and started over. Even senior teachers seemed unable to respond spontaneously to unexpected movements by their partners. Thus, it seems to me that perfection of the form rather than an ability to improvise freely is the aim of the school.

Their naginata is a very light, relatively short weapon, held in a rather narrow grip at one end of the haft and whirled around a central axis. The curve of the blade is not used to deflect attacks of the sword, and the cuts and thrusts are straight. Almost all the forms are oriented towards practice for the naginata, with the sword merely receiving attacks. There are also a few collateral forms featuring a highly stylized practice of the chain-and-sickle against the sword. The spacing between the partners is such that it is unlikely that the sword would be able to strike a damaging blow in most circumstances.

Despite its seemingly non-combative orientation, Jiki-shin Kage-ryu first made its name in matches against kendo practitioners. Both Satake Shigeo and Sonobe Hideo became famous by their many victories in such contests. These days, Jiki-shin Kage-ryu no longer emphasizes competition against kendo practitioners, although they do still occur. Many members do participate in competitions in the modern, sports-oriented atarashii naginata (see below).

Jikishin Kage-ryu is clearly a valued part of its practitioner’s lives. Their main dojo seems to be a place of joyous health and good spirits, full of both laughter and serious, finely honed practice. This seems in keeping with Jikishin Kage-ryu’s intention to create a system that will attract large numbers of women from many differing lifestyles. Jikishin Kage-ryu has been more successful than any other martial system of the last one hundred years in appealing to a large population of Japanese women. In the forms of this system, they find a kind of semi-martial training that encourages the development of a strong, yet graceful femininity.

The Birth of Modern Competitive Martial Sports

The Jikishin Kage-ryu exemplifies a universalistic trend that grew in the Meiji period (1868-1912 c.e.). The late Meiji era was the first time the Japanese thought of themselves as having a national identity. Before the Meiji period, one’s feudal domain was, in many senses, one’s country.

The government began to manipulate the doctrines of bushido to make them apply to the entire populace rather than just the warrior class. Through this, the government encouraged the development of a regimented and obedient society. Language, religion, and education were brought under centralized control. The dogma of the day elevated the Emperor to the status of a god. Shinto was also perverted into a state religion, professing a pseudo-history that was used as a rationale for the “manifest destiny” of Japan as the ruler of Asia. Following the same pattern of activities as the European and American imperialist powers, these sentiments carried the country through a war with Russia, the rape of northern China, and the horrors of World War II. Loyalty to the Emperor replaced loyalty to a daimyo (clan leader).

Used as a rallying point, this loyalty created an entire nation that was willing to live and die in the service of any cause deemed worthy by the government. The newly created grammar school system became a great propaganda machine. The primary emphases were on submission to the Emperor and gaining skills and knowledge for the good of the state. Students were taught that cooperation, standardization, and the denial of personal desires were the most productive ways of serving the nation.

Around 1910, martial arts practice was made a regular part of school curricula. The classical disciplines, however, were not considered completely suitable for the training of the mass population. The older martial traditions encouraged a feudalistic loyalty to themselves and their teachings and, in addition, often focused on somewhat mystical values not directly concerned with the assumed needs of modern Japan.

For this reason, judo and kendo, both Meiji creations, were taught in boys’ schools. Kendo had been standardized by teachers of some of the major traditional systems of sword fighting for the purpose of specializing in competitive training. The length and weight of the shinai (split bamboo replica sword) was fixed–rather longer than a real sword–and the protective clothing was standardized. The head, sides of the trunk, the wrists, and a thrust to the throat became acceptable targets. All other strikes and thrusts, no matter how potentially lethal did not count for points.

Kendo developed from competitive practices with protective equipment called uchiaigeikko (striking-together practice) developed in a number of different sword schools. This method became a relatively safe way to gauge each other’s skills when compared to the only other alternatives: a duel, using wooden or edged weapons or a rather abstract evaluation of an individual’s forms. Conservative martial artists, however, found this competitive style to be absurd. With such safety equipment and body armor, one could take all sorts of “risks,” diving in to strike while allowing the edge of the opponent’s “weapon” to slide across the femoral artery or the back of the neck with no thought to the fatal injury one would suffer were one dueling with real weapons. Without the fear of either losing one’s life or the dread of physical pain and injury, the conservatives felt that people moved unnaturally both in body and in spirit, becoming sportsmen rather than warriors. The innovative practitioners felt, on the other hand, that in the absence of warfare or other conflict, kata training had degenerated into a sterile repetition of forms. Such innovators saw more conservative types as simply repeating a dull round of stereotyped movements offering no means of testing the validity of their techniques, nor any insight into how they might perform with an opponent not “colluding” with them. As time passed, some ryu, such as the schools associated with Itto-ryu and Jikishin Kage-ryu became famous for their strong practice using protective equipment. Others, such as Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto-ryu, never attempted to integrate this method into their practice.

In the early Meiji period, there was another impetus for the development of competitive martial sports This was the phenomenon of roving martial “carnivals” known as gekken kogyo (gekken means “attacking sword”; kogyo means “a show”). Some former samurai, down on their luck, joined forces in traveling exhibitions, giving demonstrations and taking challenges from the audiences. Mounting the stage, fighters would challenge all comers from the audience, using wooden or bamboo swords, naginata, spear, chain-and-sickle, or any other weapon selected by the challenger. These fights were very popular and well written up in the newspapers. Although the fighters probably tried to exert some control, there were many injuries. In addition to challenge matches, members of the troop would engage each other in “combat,” and among the most popular would be a woman with a wooden naginata against a man armed with a wooden or bamboo replica of a sword.

One of the most remarkable of these women was Murakami Hideo, who became a seventeenth-generation headmistress of Toda-ha Buko-ryu. The little that we know of her life-story cries for a novel in her name. She was born in Shikoku in 1863 and as a young girl studied Shizuga-ryu naginatajutsu. When her teacher died, she moved to another area to study Ippon Sai Ichiden-ryu. Still in her teens, she left her home and went to Kyushu, wandering from dojo to dojo. At one point, she studied a form of Shinkage-ryu. Then she continued her travels in Honshu, traveling alone, testing her skill against other fighters, studying as she went. Imagine a tiny, young woman, little more than a girl, marching through the Japanese countryside, alone, without employment, walking from one dojo to another. This was a time when women were severely restrained in their choice of lifestyle and employment, but Murakami went her own way, inviolate.

She reached Tokyo while in her early twenties and became a student of Komatsuzaki Kotoo, and possibly Yazawa Isao, the fifteenth- and sixteenth-generation teachers of Toda-ha Buko-ryu. By now, Murakami was very strong, and she was awarded the highest license (menkyo kaiden) in the school while still in her twenties. She opened a dojo in the Kanda area of Tokyo called the Shusuikan (Hall of the Autumn Water).

Murakami was unable to read or write, so she was not able to make a living. At some time, then, she joined the gekken kogyo. Fighting with a chain-and-sickle or naginata, she took all challenges from the audiences. There are no reports of her ever losing. In her later years, she was able to make ends meet as a teacher, but she was always poor. According to those who knew her in her old age, she was a tiny, kind, but wary women, always ready to invite you to supper. She could drink anyone under the table. As far as is known, she lived alone and she died alone.

As these matches were for the entertainment of a paying audience, they soon degenerated to what must be considered the pro-wrestling or “Ultimate Fighting Championship” of the Meiji period with waitresses serving drinks in abbreviated kimono and drunken patrons cheering in the stands. Matches became dramatic exhibitions, vulgar parodies of the austere warrior culture from which they had emerged. Discouraged by the police who regarded them as a threat to public order, the gekken kogyo disbanded within a few years. Nonetheless, they can be regarded as the first precursors of modern martial sport in Japan–competition for the sake of comparing skills and entertaining an audience.

Copyright ©2002 Ellis Amdur. All rights reserved.

[Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5]

This article first appeared in Journal of Asian Martial Arts, vol. 5, no. 2, 1996. It has been extensively revised for inclusion in Old School: Essays on Japanese Martial Traditions.