Takuan Soho was a renowned priest of the Rinzai Zen sect of Buddhism. He lived from 1573-1645, the end of the Sengoku Jidai (Era of Warring States) through the founding of the Tokugawa Shogunate. A time of most extraordinary events and people, many of whom influenced the course of Japanese history for hundreds of years, he influenced these men in turn. A religious teacher, painter, poet, calligrapher, gardener, and tea master, Takuan was familiar with all sorts of people and was able to reach all of them. Among the

people he touched was the official swordsmanship instructor of the first three Tokugawa shoguns, Yagyu Tajima-no-kami Munenori, the youngest son of Yagyu Sekishusai Munetoshi, founder of Yagyu Shinkage-ryu hyoho (strategy and swordsmanship).

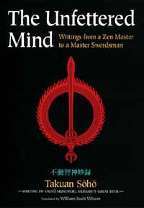

The Unfettered Mind is an excellent translation of several of Takuan’s most significant works on Japanese martial arts. Even today, they are read by Japanese for their profound insights of the human condition and on the proper way to live one’s life.

The first of these, Fudochi shinmyoroku (here, The Mysterious Record of Immovable Wisdom) is a letter from Takuan to Munenori. It deals with the myriad practical, technical, psychological, and philosophical aspects of combat. It goes beyond them, however, to discuss how the swordsman can, by concentrating on his art, become an integrated human being.

The second essay in this collection, Reiroshu (The

Clear Sound of Jewels), discusses the basic nature of humanity and how to discern what is correct and what is merely a product of personal desire, and extends the argument to knowing how to understand the balance of life and death and, very important for a warrior serving a feudal lord, when and how to die.

The final piece, Taiaki (Annals of the Sword of

Tai-a), is an examination of the psychological aspects of combat, particularly in dealing with oneself and the opponent, and of overcoming the tendency of the

mind to delude itself. In combat, this would lead to the exponent’s death; in life, it precludes the individual from attaining a clear understanding of the nature of reality and attaining ultimate freedom from causality.

These essays are pretty deep stuff, not “easy” reading, but Wilson’s translations of these works are crisp and written in a way that modern people, especially here in the West, should find relatively accessible. He supports his translations with excellent notes and gives readers the cultural and historical context that is so necessary to understand their profound truths.

Highly recommended.