“They’re waxing our floors tomorrow; can you help me move a bed?”

I wondered how much bed it could be that had Chris Bates calling for my assistance. Given his house full of Chinese and other Asian furnishings, I should have been more cautious. Bates, his wife and daughter and I spent the evening struggling with a Ch’ing Dynasty behemoth with a canopy, a bed the size of a horse trailer, a bed like something out of “The Last Emperor.”

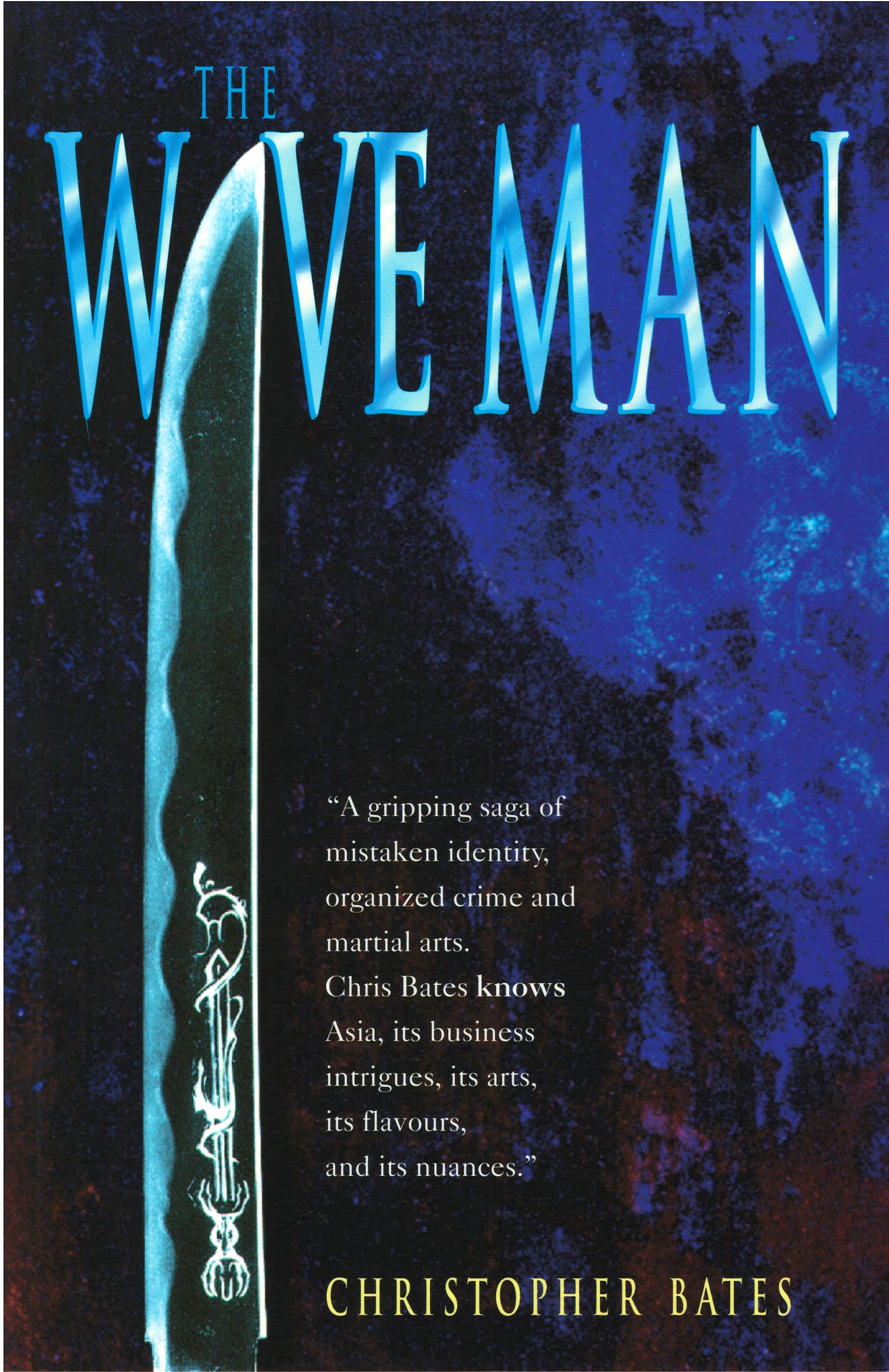

When he wasn’t moving museum piece sleeping accommodations, Chris, very expert in more than half a dozen Asian combative disciplines, spent a lot of time bouncing me around his yard. We spent a lot of time too, afterwards, drinking tea from his collection of tiny Yixing pots, talking about the fighting arts. Bates is back living in his beloved Asia now, and he’s written a wonderful novel there, The Wave Man.

When you see it in the bookstore [unfortunately, you’ll no longer find this book in bookstores–fortunately, it is available exclusively through Koryu.com.], The Wave Man will be shelved along with the company of a whole spate of Eric Lustbader-type fiction. Oriental intrigue. Vast crime conspiracies. Sex and violence, both in forms exotic, both in exotic locales. It’s a book to be stained with suntan lotion during a summer beach read or savoured with hot chocolate on a winter’s night.

Ted Bergman, a young American businessman living and working in Asia, is the title’s “wave man,” a reference to the ronin, those pariah members of the samurai caste who had, for one reason or another, lost their place in society and usually lost themselves in the process. Bergman, whose adolescence was spent in Japan, has absorbed much of Japan there. It is not so much an alienation from this nurturing culture that has made a wave man out of Bergman; he has, in growing up, survived a tragic love that has changed him in ways more than he knows, left him adrift in more than one sense of the word.

Ted Bergman is a character of the sort once described as having been “out East too many years.” Sit in a hotel lobby a while in Bangkok, Taipei, or Tokyo and you will see his real life kind: Westerners who’ve been East too long, pursuing business or love or something of the spirit, people whose souls are caught somewhere in between and who can’t really be happy in either place any more. They are called “Old Asia Hands” and stir a romantic imagination. But expatriates like Bergman have psyches unanchored and floating at sea somewhere out on the International Date Line. Bates knows them well; it shows in his writing.

The random waves that have bobbed Bergman into adulthood suddenly bring him into a sinister current. Corruption in his trade swirls with yakuza drug dealing and before long Bergman is running quite literally for his life and the waves upon which he has ridden aimlessly for years have become a dangerous whirlpool, spinning him back into his own past.

The Wave Man is remarkably well-written for a first novel, full of engaging and colourful characters, evenly spaced, seasoned with accurate descriptions of Asian places and lots of action. Bates handles dialogue like a pro.

These literary considerations, however, are not what should have martial arts readers picking up this book. What separates this new novel from so many others in the genre is that its author is writing from the inside.

Unlike Lustbader and others, Bates has sweated and bled in training halls in Taiwan, Singapore, and elsewhere. He is fluent in Mandarin; just as conversant living in the climes he writes about. Such knowledge and experience make The Wave Man a more entertaining and valuable read, not just because Bates avoids the egregious technical blunders others make in writing about the martial arts or the East. This book will engross practitioners because Bates understands much of what really motivates, guides, and plagues the modern martial artist.

Bergman, for instance, a martial artist since his childhood, doesn’t train as often as he knows he should. Not because of some dramatic mystery; he’s slacked off his practise because he’s lazy and too busy trying to make a living. Sound familiar? He is prodded to return to the Way by a sense of what the Japanese call giri, obligation to those who’ve taught him, by a certain knowledge that refocussing his life on these unique arts is a real way to refocus and recommit the self. These are matters not readily appreciated by those who have never learned an Asian combative art, steeped in tradition, obligation, and a profound sense of purpose. But they will ring as the truest of elements in The Wave Man’s plot for those who have travelled along a martial Path.

It’s enjoyable to read fiction by someone who knows his readers as well as his storytelling craft. And in this regard, The Wave Man will not sit on the shelf with those other books. It stands out convincingly.

If you didn’t risk bodily harm helping Chris Bates move his legendary bed, you probably won’t receive a much-deserved copy of his new book but you can order it [and you can read an excerpt of it here on the Koryu.com website.]