The Role of the Arms-Bearing Women in Japanese History

Women’s Martial Training in Modern Times

As martial arts continued to be integrated into public education during the first decades of the Showa period (1926 to 1990 c.e.), the practice of naginata came to a crossroads. Judo, kendo, and, later, karate were made to be practiced in a standardized form. Naginata training, however, was still confined to the adaptation of specific ryu to physical education classes.

When taught to groups of young people, however, even the most traditional ryu must change. I have seen pre-Second World War photographs of a variety of koryu taught en masse, with lines of children diligently swinging weapons in unison. Other pictures show young children phlegmatically plodding their way through kata. Form practice means something very different to warriors trying to get an edge in upcoming battles than it does to young teenagers attending gym class at the local high school. Therefore, competitive practice became more and more popular not only as a means of training, but also as a way of holding the interest of young people who, understandably, could not see the value of kata practice alone. In competition, a light wooden naginata covered with leather was first used; later, for safety, bamboo strips were attached to the end of a wooden shaft in imitation of kendo shinai. This replica weapon is light and whippy, allowing movements impossible with a real naginata. As rules developed and point targets were agreed upon, the techniques useful for victory in competition began to differ from those used by the old schools, each of which had been developed for different terrain and varied combative situations. Naginata practice began to develop into something new–a competitive sport.

Not all teachers were opposed to this universalistic trend, given its congruence with the strong centralization of state power at this time. During the Second World War, some naginata teachers, notably Sakakida Yaeko, in conjunction with the Ministry of Education created the Mombusho Seitei Kata (Standard Forms of the Ministry of Education). Sakakida had been, and remains, a practitioner of Tendo-ryu and was an avid competitor in naginata matches against kendo students. She states that she found that the different styles of the old ryu were not suitable to teach to large groups of schoolgirls on an intermittent basis. Given the conditions in which she had to teach, she felt, also, that it was too difficult for the girls to learn the sword side of the kata, so she began to emphasize solo practice with the naginata. Finally, she was concerned that they might study one ryu in primary school and another in secondary school, thus being required to relearn everything each time they switched schools.

As a result of these difficulties, she and several associates created totally new kata that focused upon the naginata against naginata. This combination is not unknown among koryu, but it is rather uncommon. Notable ryu that focus upon dual naginata practice include Toda-ha Buko-ryu, Higo Ko-ryu and Seiwa-ryu. Naginata instructors of traditions which emphasized the naginata against the sword could not, however, be forced to abandon their schools to enter one of the few, often obscure traditions that did have dual naginata forms. No one could imagine that teachers who had invested years, even decades, of training in one tradition would join another that was suddenly appointed the standard bearer by the state. Most systems emphasizing more than one weapon were almost unteachable within the school environment. Yet the needs of society and the state that dictated those needs seemed to require an efficient, simple method of teaching youth en masse. The Mombusho forms, made for the express purpose of training school children, were the result. The Mombusho adopted these kata in 1943.

Something however, seems to have been lost in the process. Geared for children rather than warriors, these forms are, as a result, simplistic and somewhat lacking in character. The singularity that made the old ryu strong was sacrificed in favor of a generic mean. Teachers and students of the classical ryu received scant instruction in these new forms and were assigned “territories” made up of several grammar schools. As part of their preparation, the teachers were instructed in how to give “pep talks” to the girls. These talks included warnings about the barbarism of invading armies and the need for girls to protect themselves and their families. But the protection was not intended for the integrity of the girls themselves, but as “mirrors of the Emperor’s virtue.”1

Nitta Suzuyo, nineteenth-generation lineal successor to Toda-ha Buko-ryu recalls teaching these forms to girls from twelve to seventeen years old. Still a young woman herself, she was dispatched to instruct as her teacher, Kobayashi Seiko preferred to continue to teach her traditional ryu in private. As part of the training for teachers, Nitta was told that the most important thing was to boost the girls’ morale and strengthen their spirit in case of an enemy landing. She said that the girls liked the training, which was done in place of “enemy sports” such as baseball or volleyball.

Women were said to personify the spirit of bushido because their “nature” was to be selfless and nurturing. They were believed to be the basis of society because of their place in the education of children. It was claimed that martial arts training would develop the attention to details needed for housekeeping, food preparation, caring for the sick, and making a “friendly atmosphere.” A woman trained in naginata was supposed to be soft but strong, willing to be selfless but decisive, and above all, patient and enduring. The strong body she developed from training was necessary to keep healthy and active to carry out all her work. She was said to have a “full spirit” and strong beauty. One teacher’s manual, written in the middle of Japan’s war years, states, “the study of naginata, home economics, and sewing would develop the perfect woman.”2

In 1945, the war finally ended. The occupation forces were fearful of anything that seemed to be connected to Japan’s warlike spirit and they banned martial studies. Thousands of swords were piled on runways, run over with steamrollers, and then buried under concrete construction projects. Donn Draeger recounted to me the sight of those swords, flashing in the sun in shards of gold and silver, crackling and ringing under the roar and stink of the steamrollers.

After a eight years, however, these bans were lifted and the first All Japan Kendo Renmei (Federation) Tournament was held in 1953. At a meeting held afterwards, Sakakida and several of the leading naginata instructors of Tendo-ryu and Jikishin Kage-ryu made plans for the institution of a similar All Japan Naginata-do Renmei. It was decided to adopt the Mombusho kata as the standard form of the federation, with only a few minor changes. They also decided to eliminate the writing of naginata in characters (long blade) and (mowing blade) and, to indicate their break with the past, spell it in the syllabary whose letters have only sound values. This martial sport has come to be called atarashii naginata (new naginata).

The change of characters in writing “naginata” may seem to be a trivial one, but it is not. The philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty refers to language as “sublimated flesh.” By this, he means that language is the concentrated essence of human existence and determines how life will be lived. This change in how “naginata” is written states decisively that atarashi naginata is no longer a martial art, using a weapon either to train combat skills, or to demand, through its paradoxical claim as a “tool for enlightenment,” a focused and integrated spirit. Instead, they have created a sports form, martial in both appearance and “sound,” but not in “character.”

Atarashii naginata is composed of two parts: kata and shiai. According to some of its leading instructors, particularly those of this generation, the kata were created by taking “the best techniques from many naginata ryu.” Perhaps some may feel that I am stating this a little too strongly, but this is an absurd idea. The forms of the various ryu are not mere catalogues of separate techniques to be selected like bon-bons in a corner candy store. They are interrelated wholes, permeated with a sophisticated cultivation of movement, for combative effectiveness and/or spiritual training. Sakakida herself only states that she observed the old ryu and tried to absorb their essence. Then, forgetting their movements entirely, she devised the new kata.

These first-level kata, derived from the Mombusho forms and now called shikake-oji, are a set of simple movements requiring straight posture and sliding footwork. Practice is done with an extremely light shinai or wooden naginata.

These forms are used in kata contests. Two pairs of contestants perform the same kata, and they are judged on the “correctness” of their movements. There is a second level of forms, called the Zen Nihon Naginata Kata, which is only taught after a student reaches third dan level. Some claim that they are the product of a study of the naginata kata from fifteen different martial traditions. A committee of members of the Naginata Renmei allegedly derived what they considered to be the essential movements of these ryu and combined them into a linked set of seven kata. However, according to martial arts scholar, Meik Skoss, the forms are, in fact, largely made up of techniques from Tendo-ryu and Jikishin Kage-ryu.

Not all of the old teachers are enamored of atarashi naginata. Abe Toyoko, a senior instructor of Tendo-ryu, in a marvelous interview in “Fighting Woman News” discussed these forms with Kini Collins in the early 1980s. Abe Sensei was one of the strongest of all the strong women in Tendo-ryu and had always been rather a lone wolf. Japanese social groups can be rather wearing, and Abe Sensei was well known for her blunt speech and strong opinions. Her almost gruff power was reflected in her art and her words. The first time I saw her in a group of other Tendo-ryu instructors, she stood out like a mother bear. She never seemed to try to look pretty or graceful–simply effective.

This new stuff. One, up with the stick. Two, down with it. Three, put it away. Well, that is one way of teaching, but there is something else, I only know it as kokoro (heart, spirit). Pull it in on one, out on two, lift on three, well, you try it! If you do it only with an awareness of moving and no concept of kokoro, you are so wide open it isn’t even funny. This is what I want to teach. How to react when your partner doesn’t respond in the way you are used to. This is what it hasn’t got, the new naginata. There is no thought outside the form, there isn’t even any path for this kind of thinking.

When they got started about twenty years ago, they wanted to get going fast, so it was forced: trying to bring everyone into the same line, changing everyone’s style to fit a new form. Taking from the right, from the left, trying to get everyone to agree. Just to get started, never mind the outcome. But all these schools and the techniques themselves are separate entities governed by separate principles of movement and thought. This new thing has absolutely none of these principles.

Teaching the form of a technique rather than the substance and form leads to nothing. Worse than nothing. Some teachers say that form is enough for women. No way! That really makes me angry. Who needs form? In Japanese, there is a word, rashikute (to seem or to be like something), like a woman, like a man, like a …I don’t know what, but it really colors our language. It has meaning though, not just the surface stereotypes. A woman’s whole life is being womanlike. To be like a woman is not simply to be soft. To be womanlike is to be as strong or as soft, as servile or as demanding as a situation calls for. Be appropriate and act with integrity. This isn’t being taught at all. And it is the heart of budo, it is alive in the practice of it.3

The atarashii naginata competitions are an imitation of those of kendo. Sadly, the matches often resemble a game of tag with the shinai. It is striking to see how few of the kata movements are utilized by the practitioners. The kata movements, thus, are not relevant to the other wing of the system.

The contestants are well armored, but there are only eight designated targets: the top of the wrists, the top and sides of the head, the throat, the sides of the trunk, and the shins. Winning points are decided by referees. Considering that the bamboo end of the shinai is supposed to represent the blade of the naginata, the contests are often a little confusing for outsiders. Many potentially lethal or incapacitating strikes go unheeded because they do not represent a “point.” In addition, the ishi-zuki (butt) of the shinai is rarely used in such competitions, although it was an essential component of the use of the weapon in real combat. Because one scores by striking target areas with an extremely light replica of a weapon, the emphasis is on speed. The contestants hold their bodies upright on the balls of their feet to slide and jump in and out quickly, footwork suited only to the polished floors of gymnasiums and dojo. Because there is no sense of danger or even a need to protect undesignated targets, many competitors do not move or respond in a natural way. Blows that would sever arms, disfigure, or even kill are ignored because they are not designated targets. Again, consider the words of Abe Toyoko:

Our matches didn’t have all that quick jumping and dancing. They never did. There has to be a lot of aware-ness before and during a match. You can’t just enter one casually. Naginata were weapons with blades that cut, and we have to keep that respect even with the bamboo blades we use today. The first tournament I saw my teacher in, it was amazing. She walked her opponent all the way across the hall, from the east side to the west side, not using any technique, just her stance and spirit. Everyone, even the old teachers were enthralled. Then she moved to cut, just once. And I was hooked. She found my timing and caught me. She won the match too.

By removing the considerations of one’s own death and one’s responsibility for the other’s fate, atarashi naginata may have removed the major impetus for the development of an ethical stance. All that may remain for many trainees is a sport with the emphasis on winning or losing a match.

Many naginata-ryu teachers have entered the modern association and have attempted to teach both their old traditions and atarashi naginata. However, only a few of their students are willing to practice the old ryu. These martial traditions, with footwork suited to rough terrain and low postures suited to exerting leverage in cutting and protecting all of the body, seem to be awkward and old fashioned to atarashi nagi-nata students who focus on modern competition. This has resulted in the abandonment and demise of most of the old martial traditions within the last fifty years. Often the only reason young people practice the old school at all is “just so it won’t be forgotten.”

When searching out old schools, it was disheartening to see how many schools who had made common cause with atarashi naginata, rather than getting new students, ended up with none. In the early 1980s, it took three months of concentrated effort to locate Sakurada Tomi, the eighteenth-generation headmistress of the Suzuka-ryu, one of the foremost naginata instructors in Japan, the last headmistress of her tradition. Numerous calls to both the local and national offices of the Atarashi Naginata Association were met with indifference, although she had been perhaps the most significant figure among women martial artists in Sendai city. We finally located her, alone, without students or family.

With the “official line” trivializing the classical schools to young impressionable students, the older ryu, with the exception of Tendo-ryu and Jikishin Kage-ryu, are largely ignored, except to be invited to give demonstrations at the intermissions of atarashi naginata competitions. Among the traditions that have almost or completely died out in the last twenty years, we must number Choku Gen-ryu, with its massive nine-foot-long naginata, the vital and powerful Suzuka-ryu and elegant Anazawa-ryu. The dynamic Muhen-ryu, another school that interestingly uses naginata and bo (long-staff) interchangeably within the same forms, is also largely ignored by the atarashi naginata students who study under its headmistress.

It must be faced, however, that much of the demise of the old traditions is the responsibility of practitioners themselves who either could not find a way to make their art relevant to the younger generation, or have no idea themselves of the value of the tradition passed on to them. Illustrative of the latter was one woman, an atarashi naginata competitor and teacher who had practiced a bujutsu ryu since childhood.

I said to her, “Your training in classical naginata must give you a real advantage in strength over the other participants in contests.” In response she complained, “No matter what I do, the naginata-jutsu techniques creep into my atarashi naginata movements and ruin it. We are all supposed to do it the same way, but I just can’t!”

This attitude, too, is countered by Abe Toyoko:

I see lots of people today, jumping from one new thing to another, not getting settled. I really think people need something in the foundation, some deeply rooted place in their lives. I see this even in the judging of naginata matches. It used to be so different, this judging. There were only two judges per match, and they were deliberate and subtle, not jumpy and conforming like the ones today. Even their movements had more meaning. The judges used to have individual styles, their own way of signaling points. Now everyone has to do it the same way. You won’t believe this. They stopped a match once, one I was judging, and asked over the loudspeaker if I would raise my arm a few more degrees when signaling. Do you believe it? And just a couple of years ago, I was judging with another teacher. One of the competitors moved, just moved a little, and the other judge signaled a point. I asked the two women in the match if a point had been made, and they both said no. But because the judge had ruled for it, it was declared valid! I haven’t judged since. I don’t want to be a part of teaching people how to win cheaply or lose unfairly.

Conclusion

From an essay in history sprinkled with only minor leavenings of personal opinion, I find it necessary to end on a truly personal note. Approximately twenty years ago, I began a project on the use and history of the naginata. The initial stages of this were done in the company of Ms. Kini Collins: I later took the project over by myself, and a series of essays, many of which are in this book, are the result.

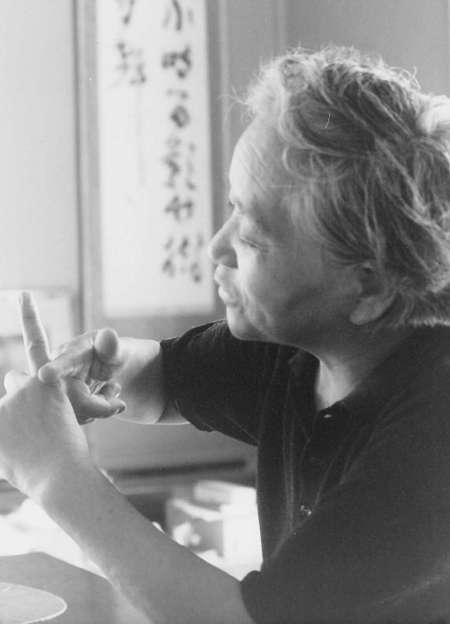

This weapon attracted me the first time I saw it, not as a “woman’s weapon,” but one suited for me, a man of six and a half feet and over 220 pounds. Araki-ryu, the first martial tradition I entered, uses both the nagamaki and a large naginata in a dramatic, almost wild fashion probably very similar to the methods of strapping foot soldiers and warrior monks in earlier periods of Japanese history.

I later entered Toda-ha Buko-ryu, and, thereafter, was able to study a system that has been led by women for over one hundred and fifty years. Toda-ha Buko-ryu is still very much an art of war, but it is a martial tradition that developed and permutated in the Edo period. It is a paradoxical art–every movement is an attack. There is no stance with the weight on the back foot, and no purely defensive techniques. Yet in its elegant, graceful movements, it shows some of the sophistication that develops in a martial art when warriors have the leisure afforded them by peace to study movement and refine it in depth. It is also imbued, for lack of a better term, with a profound feminine sensibility.

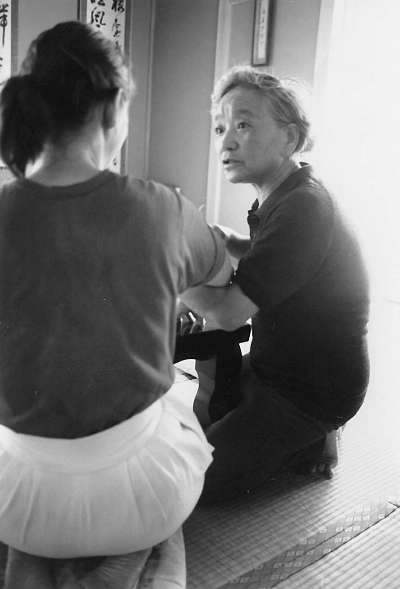

I became deeply influenced by both of these martial traditions, both in themselves and as embodied in the person of their instructors. Of most relevance to this piece is Nitta Suzuyo Sensei of Toda-ha Buko-ryu, a refined, gracious woman, unfailingly courteous and remarkably strong in every sense that really matters. The feminine leadership within this school has been a gift and a challenge to me. I have been required to model myself, in some respects, on a tiny, five-foot-tall, aristocratic Japanese woman, to learn the essence of what she offers without either slavish imitation or an arrogant assumption on my part that I can simply adapt her art to my large, Western frame. She has been a model to me in my own profession dealing with the diffusion and de-escalation of violence. It was from her that I learned the power of tact, how courtesy alone can often resolve what force of arms may not.

I have, therefore, an intense attachment and respect for the traditional koryu and firmly believe that the best of my own life’s work could never have occurred without my study in them. It is fair to say that there have been instances in which I have been able to save people’s lives using knowledge that I could have acquired in no other fashion than by training in archaic Japanese martial arts, and in none of these instances was I forced to engage in anything like hand-to-hand combat.

I believe that competitive martial sports can be wonderful activities as well. My own rather limited years of experience in judo and Muay Thai and ongoing cross-training in modern grappling systems have certainly brought that home to me. Competition can impart a sense of trust in one’s ability as well as expose one’s weaknesses. Such study can create a more self-aware individual, a person far more valuable to a community than one would imagine a mere sportswoman or sportsman to be. Thus, martial sports are not mere sports.

Atarashii naginata is a significant part of the lives of probably several million women. Something of such consequence cannot simply be shoved aside in a disdainful conservative critique that it is degenerated, watered-down martial arts. Like any other activity, martial training must continue to grow and develop if it is to remain appropriate to the times in which it exists.

However, in the rush to create martial sports that are open to anyone and useful to everyone, much of profound value is irrevocably lost. Tradition, far from being a mere nostalgia for the past, can be a powerful force to unite a people. Traditions can make people aware of their origins and singularity. Even though ryu were created hundreds of years ago to deal with problems specific to those times, there is no reason to relegate them to preservation societies or museums, mere curiosities to be trotted out several times a year as intermission entertainment during competitive matches. Since the ryu were developed for specific regions, offering specific psychological and combative methods, they can still be living traditions, strong and direct connections with the past. They were, and can be, powerful forces imparting loyalty, morality, and courage, as well as a sense of togetherness. That which helped create viable communities in the Muromachi era is still relevant today. Practiced with the intention of strengthening its community, study of any ryu can develop a cohesive courage and depth of feeling in its members. This could help maintain a community as a living entity, one not as vulnerable to exploitation or incorporation into a superficial mass culture.

Finally, the knowledge contained in the ryu was bought in blood. I do not idealize the act of killing on a battlefield. I do idolize those who passed through such experiences and, rather than leaving mere reminiscences of brutal acts committed or suffered, attempted to pass on a treasure distilled from the horrors of war: the knowledge of how to survive; a method of continuing the bonding that occurs on the battlefield well after the battle was fought, maintaining those ties of trust once the shackles of fear and rage are no longer needed to force people together; and perhaps most important, a tradition for handing on the depths of ethical and spiritual teachings contained in the heart of systems created ostensibly only for war. On my own father’s gravestone are the words of Rabbi Hillel, “In a land where there are no men, strive thou to be a man.” This is the morality learned on the battlefield, however the battlefield might be defined. This is an ethic won only through facing the potential for death: one’s own at the hands of others and others’ death at our own hands. To strive towards this ethical sense is what has led me through my over thirty years of martial training, and this is, to me, the essence of what is contained in the heart of many of the traditional ryu. For the men and women in most modern martial sports, and, specifically, for the (mostly) women who train in modern sports naginata, I believe that despite all the fine things they may have gained in the abandonment of traditional martial practice, they may have lost even more wondrous things. To wish that history were different is ultimately foolish. But foolish as it may be, I wish that they could have both.

Copyright ©2002 Ellis Amdur. All rights reserved.

[Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5]

This article first appeared in Journal of Asian Martial Arts, vol. 5, no. 2, 1996. It has been extensively revised for inclusion in Old School: Essays on Japanese Martial Traditions.

- From the Kokumin Gakko Naginata Seigi by Shigehachi Sonobe, page 7. ↩︎

- Ibid, page 7. ↩︎

- This, and all subsequent quotes of Abe Sensei were published in the early 1980s by Ms. Kini Collins in “Fighting Woman News.” The author and Ms. Collins were working on a project regarding the history of the naginata, and this interview was one of its aspects. With Ms. Collins permission, I have retained the original manuscript for this interview and have made some very minor changes in syntax for ease in reading. The meaning has not been changed in any respect. ↩︎