The Role of the Arms-Bearing Women in Japanese History

Tendo Ryu: One foot on the Battlefield, One in the Modern World

Tendo-ryu naginatajutsu exemplifies many of the most significant changes that occurred in martial training from the late sixteenth century to the present. These include:

- the transition from a warrior’s art incorporating many weapons to a martial tradition with a decided emphasis on a single one;

- the increasing perception of the naginata as a weapon associated with women;

- the transition of martial arts from combative training to a training of will and spirit;

- the use of martial arts training in mass education;

- the development of sportive forms of martial training.

The founder of Tendo-ryu is said to be Saito Denkibo Katsuhide. His original school, Ten-ryu was developed sometime in the 1560s, a time of chaos and warfare. Some traditions state that he studied with Tsukahara Bokuden, the founder of the famous Kashima Shinto-ryu. Legends of Ten-ryu assert that Saito went into retreat at a shrine in Kamakura. One night, in an incident curiously reminiscent of the Biblical tale of Jacob wrestling with the angel, he got into a fight with a mountain ascetic. After a battle lasting until dawn, Saito asked his opponent his school’s name. Saying nothing, the man walked away towards the sun. In a moment of inspiration, Saito realized the name to be Ten-ryu, “Heaven’s Tradition.”

This story is illustrative of the fact that an “enlightenment” experience does not necessarily endow an individual with any moral virtues. Saito remained a flamboyant, pugnacious man. In some accounts, he is described wearing a kimono in imitation of feathers as if he were a tengu (mountain goblin). After many duels, he killed his last opponent at the age thirty-eight. He was later ambushed by the dead man’s followers, who fired arrows from several directions. He was able to knock down many of the arrows with a kamayari (long-hafted sickle), but finally was killed, “as full of arrows as a hedgehog has quills” as one modern writer put it. Saito’s arrow-blocking method supposedly became the basis of some of the central techniques of Tendo-ryu naginatajutsu.

Ten-ryu had a rather violent history during the Edo period and quite a few of its members were involved in well-known duels with people from other schools (see Chapter 2 of Old Schools).

Like many of the ryu of that period, Ten-ryu included the study of a number of weapons–their kenjutsu, in particular, became renowned. The oldest records of the school include instructions for the study of sword and numerous other weapons, as well as battlefield tactics, fighting on horseback, hand-to-hand combat, and esoteric philosophical teachings. Over time, the ryu fissioned into a number of lines that specialized in sword, spear, or other weapons. Mitamura Kengyo, headmaster of one line in the late 1800s, singled out the naginata particularly for the training of women and girls. Mitamura’s line, at some point, began to refer to their tradition as Tendo-ryu, “The Tradition of the Way of Heaven.”

Mitamura helped organize the Seitokusha, a school of Shinto and martial arts practice in an effort to combat the steady influx of Western influence. In 1895, his group merged with the Dai Nippon Butokukai, a national regulating body of martial arts. After displaying his methods for group teaching in 1899, he was contracted by the large Doshisha women’s school in Kyoto to teach on a regular basis. Women took prominence as teachers (most notably, Mitamura’s brilliant wife, Mitamura Chiyo), and the practice weapon was made lighter.1

There are 120 two-person kata surviving, featuring the naginata, sword, kusarigama, jo (mid-length staff), two swords, and short sword. The person in the teaching position, called uketachi (receiving sword), is always armed with a sword. (From this point on, the uketachi will be referred to as the “instructor.”) The instructor’s function is to serve as “cooperative opposition,” thereby enabling the students to hone their skills.

The vast bulk of the forms feature the naginata as shitachi (users sword), which is the learner’s role. (From this point on, the shitachi will be referred to as the “practitioner”). It is unclear when these forms were developed, although it is quite unusual for older martial systems to contain so many forms emphasizing a single weapon such as the naginata. It is thus a fair surmise that more and more forms were probably added over time as practitioners attempted to add either their personal stamp or more sophistication to the curriculum of the school.

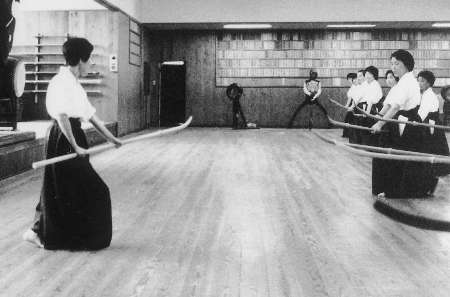

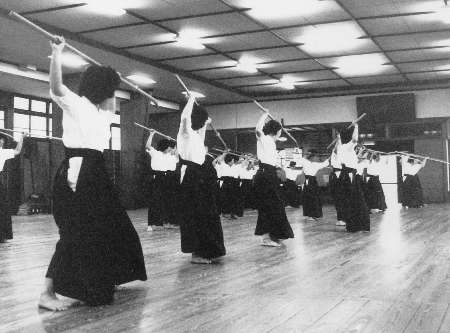

The techniques are first practiced singly and then, after a time, with a partner. Several decades ago, I observed the midsummer practice at the Shubukan Dojo near Osaka, where practitioners from all over Japan gather to train together. One of my enduring memories of this school was the sight of perhaps one hundred women, under the direction of current headmistress Mitamura Takeko, granddaughter of Mitamura Kengyo and Mitamura Chiyo, cutting and thrusting through their basic techniques in sweeping arcs of perfect unity.

The basic forms are a series of crisp, spiraling movements of the naginata against the sword. These naginata forms often utilize cuts to the wrist or underarm. Ichi monji no midare, the technique Saito Denkibo is said to have used to cut down arrows 400 years ago, forms the basis for many kata.

Although the roots of Tendo-ryu were developed during a time of war, many of the techniques of the original Ten-ryu have surely been abandoned or lost. In spite of this, the people who practice Tendo-ryu today have been able to maintain a large part of the spirit and frame of reference of those times. The kata are practiced to instill a sense of fighting awareness. Mitamura Takeko calls it the “cut and thrust spirit.” She believes that practicing in this way can help one to reach deep inside oneself. “I don’t just practice the naginata, it is a part of me.” She states that even though a student practices killing, “the gentleness and softness inherent in a woman is not lost. In fact, the training is aimed at focusing those traits into a strength which can be used for fostering and protecting as well as taking life.”

The instructor usually initiates the kata, maintaining a spacing perhaps one-half step outside that which would be appropriate to strike the practitioner. Tendo-ryu found this necessary because otherwise the naginata wielder’s movements may become cramped and abbreviated as she tried to safely accommodate her cuts so as not to strike the instructor standing within range. Thus, Tendo-ryu’s forms are geared to the development of the naginata’s technique, allowing the practitioner to cut with full power and extension.

The instructor, while trying to draw and lead the practitioner, is by no means passive. The teachers constantly remind both sides to attack, not receive. There are two main kiai, (use of the voice and breath to create or foster certain feelings or reactions in oneself or one’s opponents), one for calling or pulling your opponent toward you (TOH!) and the deciding kiai. This final kiai is executed in two ways: a short forceful “EH!” to accompany and strengthen cuts and a piercing “spiraling” manner “Eeeehhh!” to enhance thrusts. Smoothness of breath and the maintenance of postural integrity while breathing deeply are emphasized.

Some of the kata, featuring both naginata and short sword, are very realistic about the limitations of the long weapon. Since the naginata is not very effective in close fighting, it is thrown aside as the swordfighter gets inside its arc. The short sword is quickly drawn and used to stab the swordfighter. This type of form harkens back to two sources: combat grappling, in which fighters would use small weapons on the belt, and the use of the dagger by women fighting an opponent who attempted to use his greater mass and skill at close combat to overwhelm her.

Some of the senior practitioners still train in the other weapons of the school. These include techniques with the chain-and-sickle, a five-foot staff that simulates the haft of a naginata with the blade broken off, and some very intriguing forms featuring two swords.

Tendo-ryu’s main dojo is the Shubukan in Osaka, but there are powerful groups in many other areas of Japan. The members, almost all women, ranging from slender and young to stout and old, are not exceedingly formal. There is much laughter, affection, and love. But during the practice of the kata, there is a razor-sharp focus found in few dojos anywhere. Unlike some schools, which claim to have remained largely unchanged since their inception, it is likely that Tendo-ryu is far different than the original Ten-ryu practiced by the wild Saito Denkibo Katsuhide. Nonetheless, perhaps the best of his spirit still resides in the hands and hearts of the women of Tendo-ryu, a courage and integrity in movement anyone would do well to emulate.

Copyright ©2002 Ellis Amdur. All rights reserved.

[Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5]

- Larry Bieri, martial arts scholar and long-time student of Tendo-ryu, informed me that the old Tendo-ryu naginata was tapered, getting progressively wider at the butt end for better balance and a stronger grip. This practical design is no longer included in modern-day Tendo-ryu practice naginata. ↩︎

This article first appeared in Journal of Asian Martial Arts, vol. 5, no. 2, 1996. It has been extensively revised for inclusion in Old School: Essays on Japanese Martial Traditions.